Legibility, collapse, and the death spiral of American governance

The American state was built for a different scale, a different economy, a different kind of citizen. Its machinery was designed to serve thirteen colonies and agrarian interests - not 330 million people governed through platforms, proxies, and predictive sentiment models. Somewhere along the way, the civic infrastructure stopped scaling. Then it started slipping. Now it’s permanently behind.

The institutions still exist. They hold meetings, revise mission statements, send out newsletters - some of them on Substack, apparently. But their capacity to act has withered. What remains = performative continuity.

The facades are intact. The flags wave. The elections proceed. The agencies function. But beneath it all, an administrative sclerosis has set in, accumulating like plaque in the arteries of the state. The system hasn’t crashed. It’s coagulated.

This is how decline manifests in developed nations: not with explosions, but with bottlenecks. Not with fire, but with forms.

Collapse doesn’t always arrive as spectacle. Sometimes it arrives as stagnation, repeated so often it becomes tradition. Institutions persist in form but erode in function. Capacity degrades incrementally, unnoticed, until dysfunction is mistaken for normalcy - until people begin to believe this is just how things work.

By the standards of political science - loss of state capacity, erosion of legitimacy, failure to deliver basic services - the United States has already failed. Not theoretically. Operationally. The only thing keeping the system upright is the myth that it can’t fall.

This isn't about Donald Trump's second term.

It's not even about his first.

It's not about who holds the office.

It's about a decline that started decades ago.

What Does It Mean to Fail?

The Fund for Peace’s Fragile States Index evaluates countries using twelve indicators across cohesion, economics, politics, and society. These include things like factionalized elites, uneven development, group grievance, state legitimacy, public services, and external intervention. The list is clinical, almost algorithmic. Plug in U.S. metrics, and it performs well. At least, relative to Sudan.

But does its score reflect reality?

Congressional approval was 8% last year. Confidence in the Supreme Court is in freefall. Faith in electoral integrity is negative-sum: each half of the electorate believes the other side’s votes are illegitimate. Public trust in media, science, and government is at or near all-time lows. The idea of a shared national consensus is a museum piece.

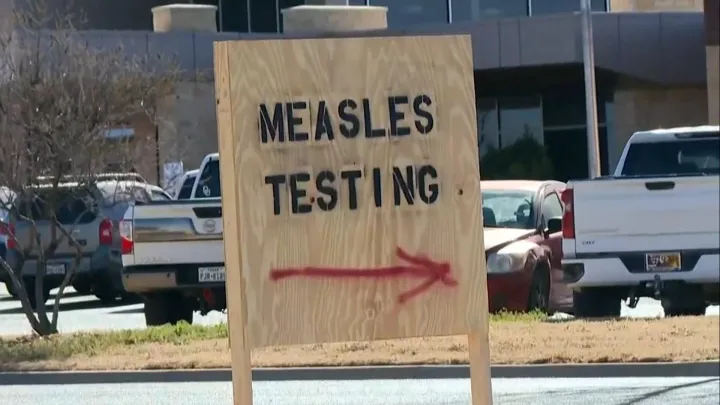

America cannot build high-speed rail, deliver clean water in major cities, or prevent bridges from collapsing. Life expectancy is declining. Medical debt is the leading cause of bankruptcy. Public schools are under siege from both underfunding and politicization. Disaster relief is Twitter-based triage. None of these are surface flaws. They are structural.

So why doesn’t America appear on the Fragile States Index as a failure?

Because it still exports liquidity, culture, and legitimacy at scale. And because the definition of a failed state implicitly assumes you’re not wearing a Rolex.

Bureaucratic Paralysis as National Identity

The California High-Speed Rail project, originally proposed in the 1980s, is now a kind of bureaucratic performance art. As of 2024, it has cost over $100 billion and still doesn’t connect San Francisco to Los Angeles. A single environmental review document ran over 25,000 pages.

Compare this to China, which built 40,000 kilometers of high-speed rail in roughly the same time period. This isn’t authoritarian efficiency, as tempting as that proposition may be as an excuse conferring moral superiority. It’s a different relationship to modernity. America’s is defensive. Each infrastructure project must survive lawsuits, political sabotage, media cycles, and Byzantine procurement rituals.

The French historian Marc Bloch wrote that institutions, like people, are slow to realize they are dying. America’s infrastructure systems aren’t dead. But they are entombed in legal amber, incapable of adaptation.

A Monopoly on Violence

Max Weber famously defined the state as the entity that claims a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. The United States has taken this concept and franchised it. Police forces operate with near-complete autonomy. ICE agents stage raids with minimal oversight. Private military contractors have carried out operations abroad and at home. During protests, cities borrow gear from the Pentagon and behave like occupying forces.

There are nearly 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the U.S. They don’t follow the same rules. They’re not interoperable. They compete for federal funding and attention. This isn’t monopoly. It’s a decentralized patchwork with wildly uneven accountability. In some towns, the sheriff is a small-town administrator. In others, he’s a warlord with a badge.

When George Floyd was murdered, the international outcry treated it as an exceptional horror. It wasn’t. It was a statistically common interaction between Black citizens and armed state actors. The exception was that someone filmed it.

If a failed state is one where the government can’t restrain its own forces or deliver justice to victims, America’s status should be clear to any rational observer.

Seeing Like a Collapsing State

James C. Scott’s “Seeing Like a State” argues that modern governments require legibility: simplified, abstracted views of society that allow bureaucracies to manage complex systems. But what happens when the people running the state can no longer read the map?

In the U.S., basic functions - like issuing driver’s licenses, running elections, or disbursing unemployment insurance - depend on 40-year-old software. When California's unemployment system failed during COVID, it lost $30+ billion to fraud. Not because of corruption, but because no one understood the codebase anymore.

The federal government still uses COBOL. State governments outsource core functions to private contractors who subcontract to other contractors, until no one is accountable and the system becomes a black box. Voters receive ballots that are illegible. Public health advisories contradict each other. Wildfires go uncontained because jurisdictions fight over whose map is “real.”

A state that cannot make itself legible to its citizens, or itself, does not govern. It lurches.

The Trident: Dollar, Myth, Interface

Why does it still appear to work? Why do we still uphold America as The World’s Oldest Democracy? The answer lies in three forms of structural suspension.

First, the dollar. As the global reserve currency, the dollar lets America borrow at fantasy rates, run deficits without punishment, and export inflation. It is the ballast beneath a leaking ship. When you can print the world’s money, your collapse timeline gets extended. But not indefinitely.

Second, the myth. American exceptionalism is a civic religion. The Founders are saints. The Constitution is scripture. The rituals of democracy - flag pins, Fourth of July fireworks, elementary school civics lessons - provide continuity even as the content they supposedly anchor decays.

Third, the interface. America still *feels* like a country. You can go to DMV websites, call 911, vote, argue on Reddit, see Supreme Court headlines. It’s like using a beautifully skinned app whose backend database has been corrupted for years. The front-end performance persists. The core logic does not.

Together, these three props allow for a condition we might call “velvet failure”: the soft, slow erosion of governance that looks like normality but functions like managed decline.

A Slow-Motion Hegemonic Implosion

To paraphrase (as much as I'd dare) Historian Ernest Gellner, nationalism is what happens when a state and a culture disagree about whose borders contain whom. America’s version of that disagreement is internal. The state believes it governs a united polity. The culture has already seceded into a hundred overlapping simulations - religious, ideological, algorithmic.

In some simulations, America is an empire. In others, a failed experiment. In others still, a corporation with a military. These simulations do not resolve. They coexist, and in doing so, render collective action impossible.

What happens when a country cannot update its shared reality? When every major institution is in epistemic freefall? When its myths are pristine, but its outputs are broken?

The answer: it keeps going. Until it can’t.

You can fool the world with good branding. You can even fool your own citizens. But - in popular parlance - the body keeps the score. Eventually, the trust deficit becomes a debt that can’t be rolled over. Eventually, the dollar loses its place. Eventually, the lights go out.

It won’t be sudden. Collapse is rarely cinematic. It’s procedural. It looks like decaying buildings and delayed permits and missing antibiotics. It sounds like voicemail systems and lawsuits. It feels like acceleration without agency.

America is not going to become Venezuela. It’s going to become something stranger: a state that performs itself convincingly even as it forgets how to function. A simulation of governance wrapped in prestige television.

And when the myth runs out, and the branding fades, what remains?

A failed state. With very good fonts.

The Index is a reader-supported, indie publication.

Now, more than ever, the world needs an independent press that is unencumbered by commercial conflicts and undue influence.

By taking out an optional founding membership, you can help us build a free, accessible, independent news platform firewalled from corporate interests.