Arc arrived in a moment when browsers had calcified into utilities.

Chrome was dominant, Safari was entrenched, and Firefox had become either a niche or a dinosaur, depending on your age/ideology.

Every incremental release looked the same. Tabs, omnibar, extensions, sync. The market had matured to the point where differentiation seemed impossible, but Arc managed to feel new.

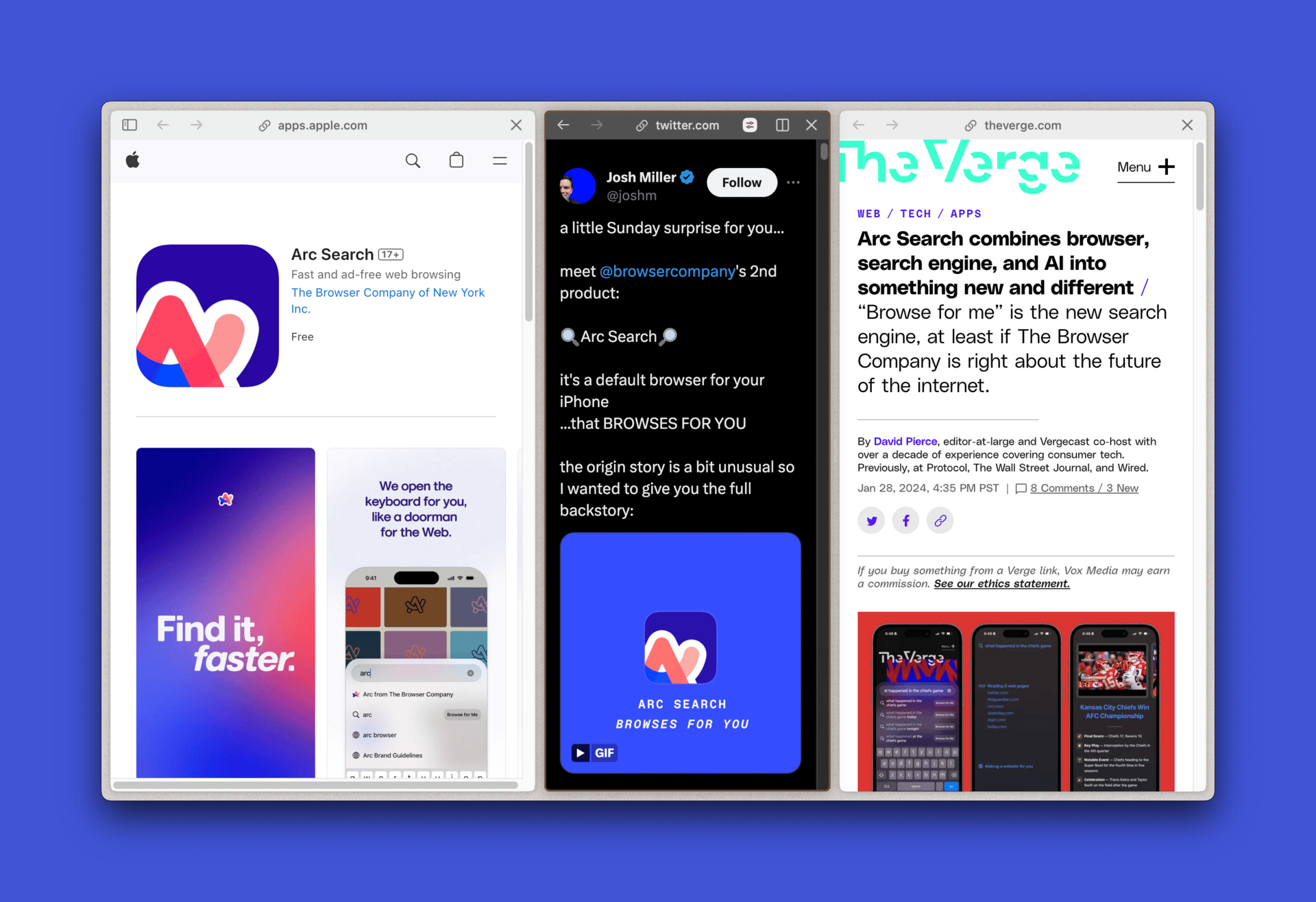

The Browser Company pitched Arc as a rethink, and at least in form, it was. Clean edges, vertical tabs, spaced layouts, and an interaction model that suggested browsing could be productive rather than chaotic. The app felt like a software artifact designed with taste. If you lived in it for a few hours, you could see how people would fall in love with it.

For a generation of users, their browser is the operating system. Slack, Figma, Notion, Google Docs, GitHub: all live in a browser tab. The idea that this shell could itself be reimagined had been declared impossible // pointless by incumbents, but here was a startup showing that it could be elegant.

Arc quickly built a reputation as the most beautiful productivity app of the decade, a consumer-grade object that suggested work software could be aspirational.

Why Beauty Matters

Skeptics often roll their eyes at design-led software. After all, Microsoft Office didn’t become dominant because of elegance. Salesforce didn’t win by looking good. And it still doesn’t.

But beauty has leverage. In consumer markets, design is differentiation. In productivity, it can be wedge. Apple normalized premium pricing in hardware by focusing relentlessly on aesthetics. Slack grew because it felt more pleasant than email, even though its functional core was a glorified chat system.

Arc fit in that lineage: beauty as strategy.

Unfortunately, history tends to punish the beautiful app. Few of them last as independent companies.

Mailbox, for example.

The reason why is structural. Beauty alone doesn’t build defensibility. Network effects, distribution lock-in, and enterprise integration will invariably outweigh the softer advantages of elegance.

For Arc, the core question was always whether design could become moat.

The Economics of Browsers

Browsers are not lucrative businesses. Google subsidizes Chrome through search distribution, effectively monetizing it as a traffic funnel.

Apple uses Safari as part of its iOS control stack, extracting rent from Google for default placement. Mozilla survives largely through its own deal with Google. That is the entire business model of the category: browsers exist to channel search queries. Arc tried to argue that productivity value could support a subscription, but that is a hard proposition in a world where Chrome is free and backed by infinite cross-subsidy.

The reality of this meant that Arc’s long-term path was narrow.

Either it would monetize through a novel mechanism - perhaps team collaboration inside the browser - or it would need to align itself with a larger enterprise that could fund its continued existence.

The beauty was undeniable, but beauty without scale economics = fragile.

The Enterprise Exit

Which brings me to the exit.

The Browser Company is being acquired by Atlassian for $610 million.

Arc selling to a large, boring enterprise software company feels anticlimactic. But it’s also logical. Software history often resolves this way: the product with taste, adored by enthusiasts, ends up subsumed into a portfolio where taste is secondary to distribution.

Think about how Microsoft swallowed Wunderlist, only to shut it down and roll the ideas into To Do. Or how Google acquired Sparrow, the beloved email client, and its DNA dissipated inside Gmail. The cycle repeats because the structural forces are consistent. Beautiful productivity apps rarely scale independently.

They need distribution, and distribution tends to belong to enterprises.

To users, this feels like betrayal. The startup that promised to make work software aspirational is now owned by a company whose aesthetic is dashboards and quotas. But to investors and founders, it’s validation. The product was good enough to command a premium from a buyer who doesn’t usually care about design.

It’s an outcome, if not the one early adopters dreamed of.

History is littered with apps that began with beauty and ended in assimilation. Sunrise was a better calendar. Mailbox reimagined mobile email. Clear was a minimalist to-do list. All three were acquired, folded in, and ultimately shut down. The underlying lesson is that design wins attention, but infrastructure wins markets.

Why is this pattern so persistent? Part of the reason is that distribution is structurally expensive. Consumer productivity tools have to acquire users one by one, and even viral growth has limits when the business model is thin. Enterprise incumbents, by contrast, can add an app to their suite and distribute to millions overnight.

The asymmetry is overwhelming.

Even the most beloved app will find it hard to compete with a bundle that IT departments are already paying for.

The Arc of Resolution

Arc’s exit fits this history neatly. It’s tempting to be cynical: yet another beautiful app sacrificed on the altar of enterprise bundling. But there is another way to read it. Beauty survives by being absorbed. The design DNA of Arc may not persist in its purest form, but elements will filter into the larger ecosystem. That’s how Sparrow influenced Gmail, or how Wunderlist informed Microsoft To Do. Users lose the standalone purity, but the market as a whole advances.

Software design progresses less through heroic independence than through acquisition and diffusion. Startups set the aesthetic frontier. Enterprises harvest those advances and spread them through scale. The cycle repeats.

The broader implication is that the browser remains structurally captive to larger platform economics. As long as search distribution and operating system integration dominate, it will be damn-near impossible for a startup to build an independent browser company. Arc’s wager was that beauty and productivity value could overcome this. The outcome suggests otherwise. Users loved it, but love doesn’t pay for servers, CDNs, and development teams.

The startup “ecosystem” (and I find myself puking in my own mouth at the word) still rewards beauty. Designers still want to work on products like Arc. Users still evangelize them. Investors still fund them, hoping that either a new model will emerge or that an acquisition will return capital.

The system is cyclical. Arc is one more data point in a long lineage.

This is how software history resolves: design innovation at the edge, absorption at the center. The enthusiasts will mourn. The investors will celebrate. The enterprise will integrate. And the cycle will continue until the next beautiful app arrives, ready to try again.